Timothy Evans was wrongly accused of murdering his wife and infant daughter, at their residence in London. Evans was later tried and convicted for the murder of his infant daughter, and he was executed by hanging in March of the same year.

During the trial, Evans accused his downstairs neighbor, John Christie, who was also the primary protection witness, of the murder. Three years after the wrong execution of Timothy Evans, John Christie was discovered to be a serial killer who had murdered several other women in the same house, including his own wife, Ethel.

The case played a major role in the abolition of Capital punishment in the United Kingdom for murder in 1965.

Who was Timothy Evans?

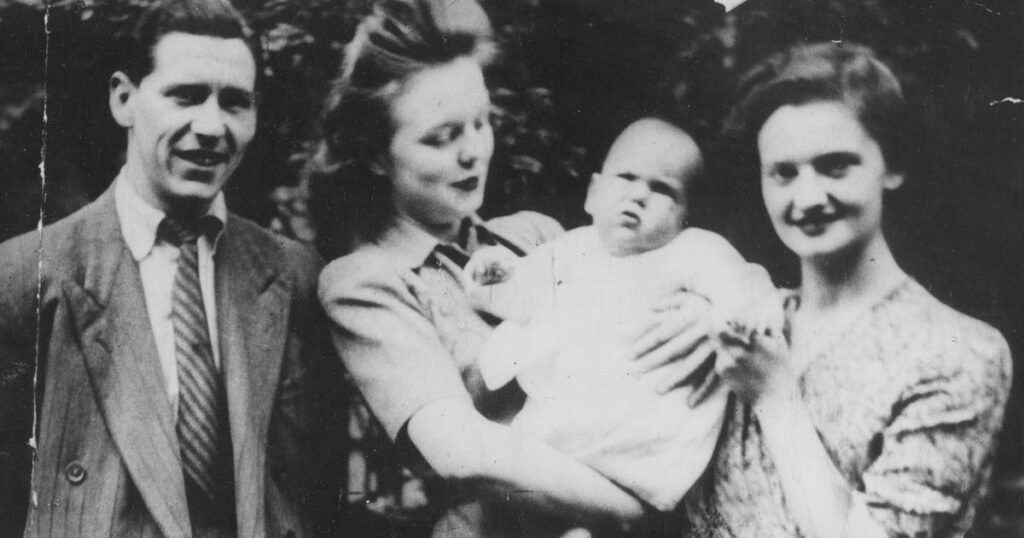

Timothy Evans had a difficult childhood because his father, Daniel, deserted his family before his birth in November 1924. He had missed a lot of school and could barely write or read. Despite this, when his family relocated to London in 1935, he found work as a painter and then as a van driver.

Evans met Beryl Thomas a few years later, and the couple married in 1947. Evans and Beryl initially lived with Evans’ mother, but when Beryl became pregnant, the couple moved out to a flat. Beryl became pregnant again in 1949, but because the couple was already struggling financially, she chose to terminate the pregnancy, which was illegal at the time.

They couldn’t go to a doctor because it was illegal, so they turned to their downstairs neighbor, Christie, who convinced the couple that he had some medical knowledge and could perform the abortion. Christie had already murdered several women at the time.

Timothy Evans was far from a perfect man; he squandered his wages on alcohol, and his heavy drinking at the time aggravated his already volatile temper. This was also the reason why his and his wife’s arguments were loud enough for the neighbors to hear, and sometimes it escalated to physical violence, which was witnessed by some on several occasions.

Beryl’s unusual death

Timothy Evans went to the Merthyr Tydfil police station on November 30th, 1949, and informed officers that his wife had died in ‘unusual circumstances.’ Evans also expressed concern for the safety of his eighteen-month-old daughter, Geraldine.

Evans first admitted to accidentally killing his wife by giving her a liquid in a bottle to abort the fetus and then disposing of her body in a sewer drain outside 10 Rolling Ton Place. He informed them that he had traveled to Wales after making arrangements for his daughter’s care. However, when the police examined the drain outside the front of the building, they discovered that the manhole cover required the combined strength of the officers.

Evans withdrew his confession

When pressed further, Evans changed his story, claiming that Christie had offered to perform an abortion on his wife. He claimed he left Christie out of his first statement to protect him. He also stated that when he returned from work, Christie informed him that the abortion had failed and that his wife would be unable to attend. Christie told him that he would dispose of the body and arrange for a couple to care for her daughter.

Christie told Evans to leave London in the meantime, and when Evans returned and ask Christie to see his daughter, Christie refused.

As a result of his second statement, the police searched 10 Rolling Ton Place but were unable to find anything useful. However, on December 2, police discovered the body of Beryl Evans, wrapped in a tablecloth, in the back garden wash house.

The only way to get into the washroom was to use a knife, which Christie had been seen using. Notably, they discovered Geraldine’s body alongside Beryl’s. It’s worth noting that Evan never mentioned his daughter’s death during his two confessions! He only mentioned his wife; he had no idea his daughter was dead until her body was discovered.

All the interviews and confessions, but the police didn’t believe a word Evans said; they manipulated and suppressed evidence not because they feared Evans was innocent, but because they knew he was guilty.

Evans third confession

When the cops showed Evans the clothes taken from his child and wife’s bodies, he was also informed that they had both been strangled. In his confession, he was informed for the first time that his baby daughter had been murdered. Evans was asked if he was responsible for their deaths, to which he replied, “Yes.” He later confessed to strangling Beryl during a debt dispute and strangling Geraldine two days later, and then he left for Wales.

Evans’ last confession and several contradictory statements made during the police interrogation were cited as proof of his guilt. Several authors who have written about the case have argued that the police provided Evans with all the necessary details for him to make a plausible confession, which they may have in turn edited further while transcribing it.

When the cops showed Evans the clothes taken from his child and wife’s bodies, he was also informed that they had both been strangled. In his confession, he was informed for the first time that his baby daughter had been murdered. Evans was asked if he was responsible for their deaths, to which he replied, “Yes.” He later confessed to strangling Beryl during a debt dispute and strangling Geraldine two days later, and then he left for Wales.

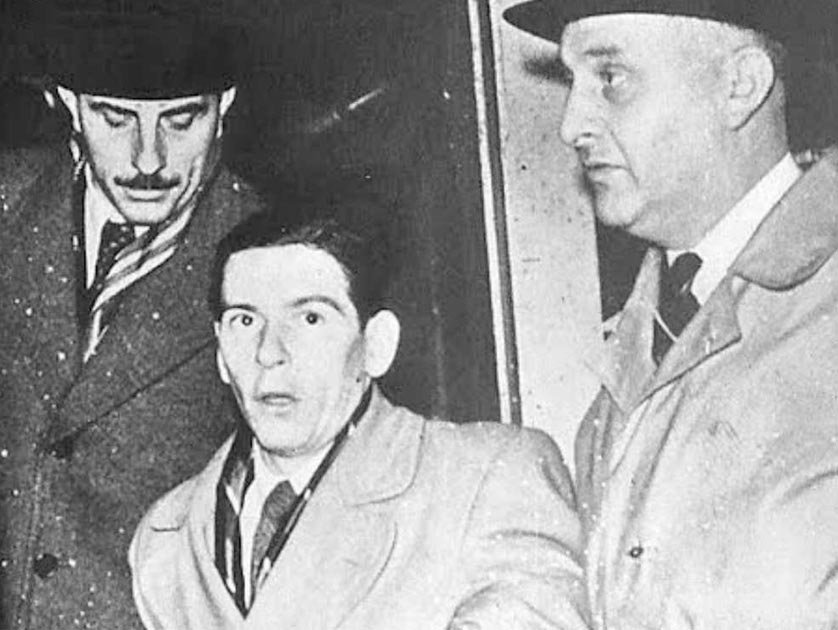

Trial of Timothy Evans

Christie denied any role in the abortion of Beryl’s unborn child and told the court about the quarrels between Evans and his wife when Timothy Evans was put on trial for the murder of his daughter on 11 January 1950. Christie and his wife Ethel were the prosecution’s key witnesses.

The case eventually came down to Christie’s word against Evans’s word, and the course of the trial turned against Evans. After a three-day trial and deliberations of less than 40 minutes by the Jury, Timothy Evans was convicted of murdering his daughter.

An important fact that was missed in Evan’s trials was that two workmen were willing to testify that there were no bodies in the wash house, why they worked there several days after Evans supposedly hid them. They stored their tools in the wash house and cleaned them out completely when they finished their work on 11 November.

The following month, an appeal against the conviction was heard by three judges, with lawyers for Evans arguing that important evidence was never put before the jury. But the appeal was rejected, and in March the 25-year-old Timothy Evans was hanged at Bentonville prison and buried in its cemetery.

The conviction and execution of Timothy Evans received little attention, but three years later the terrible truth of what actually happened at Rollinton place was revealed.

John Christie the serial killer

Three years after the execution of Timothy Evans, Christie vacated his premises and the new tenant Beresford Brown found the bodies of three women, Kathleen Maloney, Rita Nelson, and Hectorina Maclennan, hidden in a papered-over kitchen pantry, next to the wash house where Beryl’s and Geraldine’s body had been found.

A thorough search of the place turned up three more bodies, Christie’s own wife, Ethel, under the floorboards of the front room, Ruth Fuerest, a nurse, and Muriel Eady, a former colleague of Christie, who were both buried in the small back garden of the building.

Christie had even used one of the women’s thigh-bones to prop up a fence in the garden – something which the police had apparently missed when searching the property following Evans’ earlier confession.

John Christie was arrested on 31st March 1953 and during the course of questioning, he confessed to killing Beryl Evans, though he never admitted to killing Geraldine Evans.

Christie was found guilty of murdering his wife with his defense of insanity being rejected he was hanged on 15 July 1953 by Albert Pierrepoint, the same hangman who had executed Evans three years prior.

Now, the killer of Beryl Evans was finally punished, but what about Timothy? Since Evans had only been convicted of the murder of his daughter, in 1965 his remains were exhumed from Pentonville prison and reburied in St Patrick’s Roman Catholic Cemetery, Greater London.

After Christie was arrested, a campaign led by a number of prominent journalists and newspapers sought to highlight what they said was a miscarriage of Justice, but two official inquiries ordered by the home office found nothing wrong. But the campaign continued and in 1968 and new reform mind secretary Roy Jenkins recommended a royal pardon, which was accepted.

In January 2003 the Home office awarded Timothy Evans’ half-sister, Mary Westlake, and his sister, Eileen Ashby, ex gratia payments as compensation for the miscarriage of justice in Evans’ trial.

The hanging of Timothy Evans featured prominently in the campaign throughout the 1950s and 60s to end capital punishment. The campaign was eventually successful, and capital punishment was eventually abolished in England and Wales in 1969.